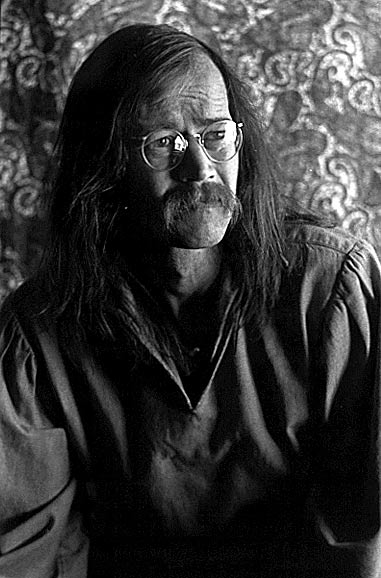

The following link and quotes are from an extensive piece about both Stephen Gaskin and the gender roles on The Farm Commune. Those looking for insight into various details should read the entire chapter, which was well researched.

As a former member of The Farm, I can attest to the accuracy of many of the quotes and suppositions.

http://www.gutenberg-e.org/hodgdon/14_Ch_04-1_ed.html

On Sexual Relations

“Gaskin taught that heterosexual union could serve as an important form of yoga: that is, a body-mind discipline that developed individuals’ capacity to focus energy from the astral onto the material plane. He referred to this sexual yoga as tantric loving or tantric balling. In conventional sexual practice, he said, men (who, we will recall, were inclined toward the “hyper–John Wayne” by American culture) tended to rush headlong toward orgasm. What was lost in this egoistic haste was the possibility that the two partners could help one another quiet their minds and concentrate their attention on the flow of astral energy through the nervous system.60 To create this meditative state, it was important to proceed slowly, beginning with a generalized, deep massaging of the partners’ musculature.”

On Marriage

“Gaskin also shocked many in the counterculture with his advocacy of lifelong marriage, but, in light of the spiritual centrality of both karmic and tantric yoga in his teaching, marriage of some sort became a necessary component of his utopia. The law of karma pointed toward the importance of fair dealing with all persons. But the intimacy and vulnerability of sexual relationships—especially those of the tantric variety—presented many ethical challenges for Gaskin and his village of believers, who sought to change the world by introducing a pure, spiritual “vibe” into worldly affairs. ”

On Mental Health

“In one Sunday-morning service, Stephen told his followers that his goal for his students was that, if he were to allow a “fairly disturbed” person to pass through the front gate unannounced, each of them would interact with the newcomer with a compassion and truthfulness that would promptly cure him or her. This musing reflected his faith that an approach to mental health modeled after the “sudden school” of Zen could cure most of the disorders that modern medicine had classified—he believed, incorrectly—as illnesses. One former member testifies that, in fact, serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, proved impervious to this approach. Yet he calls Stephen’s teaching on this point a “small-t truth,” noting that the community’s consistent application of it to cases in which former mental patients had been misdiagnosed, and had come to believe their diagnosis, yielded impressive results. “It took about a week, and people were absolutely as normal as anyone else. I saw that a lot.”

On Division of Labor

“Mothers not otherwise occupied could leave the household to volunteer for work on the farming crew, at community kitchens, the soy dairy, the canning-and-freezing facility, the community’s school, and the telephone switchboard. In place of a dial tone, Beatnik Bell’s users heard a message prepared daily by the system’s operators, detailing items available at the store, as well as the labor needs of various work crews and cottage industries. Women’s labor both inside and outside the household contributed substantially to the community, because The Farm attempted to make up for its relative lack of capital by mustering many hands.”

It’s fair to say this particular online book explores many facets of The Farm in a deeper manner than many others.